I visited the cemetery overlooking the Golden Horn and prayed for my mother and for the uncles who’d passed away in my absence. The earthy smell of mud mingled with my memories. Someone had broken an earthenware pitcher beside my mother’s grave. For whatever reason, gazing at the broken pieces, I began to cry. Was I crying for the dead or because I was, strangely, still only at the beginning of my life after all these years? Or was it because I’d come to the end of my life’s journey? A faint snow fell. Entranced by the flakes blowing here and there, I became so lost in the vagaries of my life that I didn’t notice the black dog staring at me from a dark corner of the cemetery.

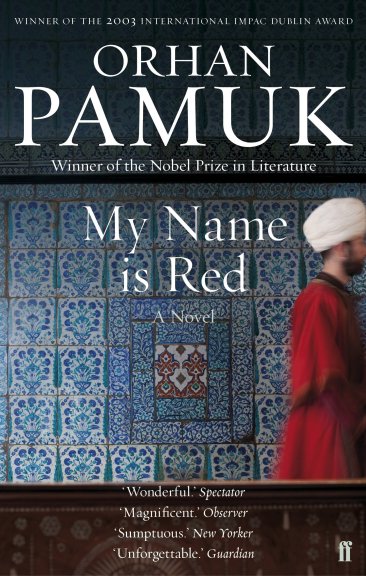

A whodunnit, written in a kaleidoscope of voices, including the murderer and starting with the murdered, My Name is Red is a book about snow. I mean, it seems to snow all the time, snow is everywhere, sometimes several times in the same paragraph. Aside from the snow, it’s confusing to start with. In fact, as I reached chapter 9, I realised that Chapters 1 and 2 were completely different people, so that reset my points and pinged me off down slightly different tracks. So I read them again and then continued, oh Pamuk, you can’t outwit me that easily. Well I mean you did. but I get there eventually.

Elegant Effendi has been murdered! I know this because he tells me in the first chapter and he’s quite annoyed and upset about it, and he really doesn’t like his murderer, or the fact that no one know’s he’s been murdered, because he’s at the bottom of a well. A couple of chapters later the murderer is talking to me, but who is it? Black is called in to try and find out what happened to Elegant by his uncle, and as he investigates the world of Istanbul’s world of miniaturists, we are presented the story through the eyes of the people he interacts with as well as himself.

It’s all a bit complicated you see. Black’s uncle, also the father to the beautiful, capricious Shekure, who everyone in the world thinks is beautiful, has been commissioned by the Sultan to create a magnificent book, in the style of the damned Franks. This goes against everything that the miniaturists, the holy men and everyone in between believe in, as well as a tradition stretching back generations. But as in all times, a few coins slipped here and there, some men’s souls do not shine so bright as the luminous reflection of a few gold or silver pieces, the book is slowly put together, without anyone but Black’s uncle seeing the whole thing. What doesn’t help poor Black is that rumours are going around surrounding this book, and a zealous preacher is inciting hatred against everything that is not traditional (now that sounds vaguely familiar). It’s not all inkwells and innuendo about artist’s quill’s though. There’s a love interest. Black is in love (as is the murderer) with Shekure. She has moved back into her uncles following advances made by her missing husbands brother but she cannot hide forever, and her two young children need a dad, is Black man enough? While navigating a murder investigation, Black and Shekure court each other through the seller of wares and local cupid Esther, one of the books more engaging characters.

Pamuk uses a highly original style in My Name Is Red that means you have to think while you read, and being a man, meaning I can’t multitask, it takes a while to get used to, but never the less, it is still hugely enjoyable. The city, it’s people, their habits, their daily chores and errands, their food are all here, observed and followed by the characters as they narrate their way around their work and the murder that has engaged even the Sultan himself.

Not just a captivating murder mystery (a genre I have zero interest in, while I was intrigued about who the murderer was, I did not work it out until roughly the same time as Black) My Name Is Red is also an intricate look at the world of miniaturist painting in Istanbul, and across the Islamic world, it’s great proponents and place in the scheme of the religion and the more earthly rulers. While each of the subjects tell us how they are the best of their time, some rail against the Frankish methods, using perspective, painting portraits, that take painting away from how God sees the world, to how people see it, ultimately making people the centre piece of art, and not God himself. Yet still there is the recognition that everything they have achieved, everything they have striven for and created will be swept away by this new style from the West, a recognition and often fear that resonates particularly loudly today.

I’ve read Pamuk’s Istanbul, which I loved, even if I thought Pamuk himself came across as a little weird, eccentric, let’s go with eccentric. But I loved his prose, his view of the world, and I wanted to read more of his fiction after A Strangeness in my Mind which I also loved. Now, I think I’ll wrap up against the snow, and read another.

Off the waterfront near Jibali, from all the way in the middle of the Golden Horn, I gazed spitefully at Istanbul. The snow-capped domes shone brightly in the sunlight that broke abruptly through the clouds. The larger and more colourful a city is, the more places there are to hide one’s guilt and sin; the more crowded it is, the more people there are to hide behind. A city’s intellect ought to be measured not by it’s scholars, libraries, miniaturists, calligraphers and schools, but by the number of crimes insidiously committed on it’s dark streets over thousands of years. By this logic, doubtless, Istanbul is the world’s most intelligent city.